2 professionals

Bioderma Congress Reports WCPD 2025

Bioderma Congress Reports WCPD 2025

Get access to exclusive dermatological services to increase your professionnal knowledge: +500 pathology visuals, clinical cases, expert videos

Benefit from valuable features: audio listening, materials to be shared with your patients

Stay informed about the upcoming events and webinars, latest scientific publications and product innovations

Already have an account? login now

Reports written by Dr Maria Florencia Martinez (Pediatrician & Pediatric dermatologist, Argentina) and Dr Paola Stefano (Paediatric Dermatologist, Argentina).

Related topics

Reports written by Dr Maria Florencia Martinez (Pediatrician & Pediatric dermatologist, Argentina)

Speaker: Enrique Salvador Rivas Zaldivar (Guatemala)

Less frequent but important systemic diseases: Dermatomyositis and Langerhans cell histiocytosis

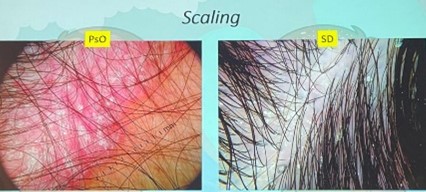

| Feature | Psoriasis | Seborrheic Dermatitis |

|---|---|---|

| Scale | Silvery-white, thick | Oily, yellowish, or dry |

| Plaque | Well-demarcated | Poorly defined |

| Erythema | Prominent, especially beyond hairline | Less well-defined, more subtle |

| Itching | Present | Also present → may cause scratching lesions |

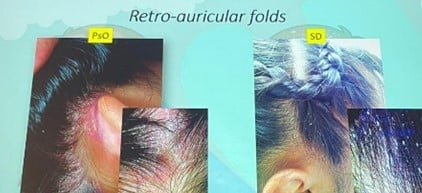

| Retroauricular Involvement | Common | Less frequent |

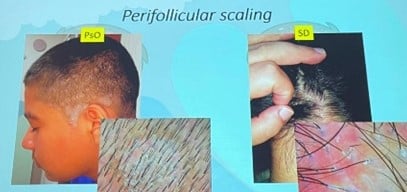

| Peripheral Scaling | More in SD, scaling follows hair shafts |

Seen in SD, rarely in psoriasis |

Note: Both diseases may present erythema and scale, making clinical diagnosis difficult in isolation.

Even histology can be inconclusive in some overlapping presentations.

That’s where dermatoscopy (trichoscopy) becomes essential.

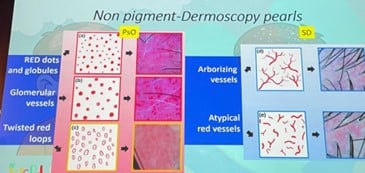

Vascular Patterns – The Key Differentiator:

| Dermatoscopic Finding | Psoriasis | Seborrheic Dermatitis |

|---|---|---|

| Vessel Type | Red dots, glomerular vessels, twisted red loops |

Arborizing blurry vessels, atypical patterns |

| Localization | Superficial dermal capillaries |

Deeper and less defined vessels |

| Scale Appearance | Thick, dry, White | Yellowish, greasy |

(Bruni et al., 2021)

Contributing factor: Malassezia spp. overgrowth in all age groups

References:

- Bruni F, et al. Clinical and trichoscopic features in various forms of scalp psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021 Sep;35(9):1830-1837.

- Silverberg NB. Scalp hyperkeratosis in children with skin of color: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Cutis. 2015 Apr;95(4):199-204

- Waśkiel-Burnat A et al. Differential diagnosis of red scalp: the importance of trichoscopy, Clinical and Experimental Dermatology, 2024, Setp; 49 (9): 961–968

- Kim GW et al. Dermoscopy can be useful in differentiating scalp psoriasis from seborrhoeic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2011 Mar;164(3):652-6

Speaker: Arturo Lopez Yañez Blanco (Mexico)

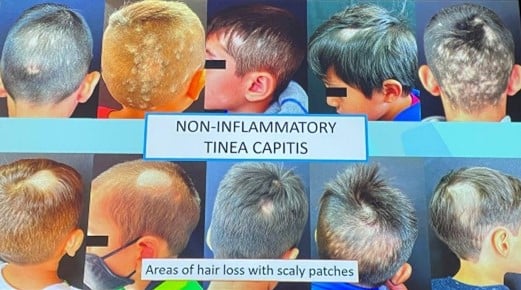

The speaker began with a general overview of tinea capitis emphasizing that it's a fungal scalp infection mainly affecting children (98%), caused by dermatophytes of the Trichophyton and Microsporum genera.

Epidemiology & Clinical Forms

The etiological agents vary by region: M canis, T tonsurans, M audouinii, T mentagrophytes, T verrucosum.

Two main clinical forms:

|

Inflammatory tinea capitis

|

Non-inflammatory tinea capitis |

| Tender plaques with pustules and crust |

Single or multiple hair loss patches

|

| Painful abscess | Scaly patches |

| Lynphadenopathy | Pruritus |

Diagnostic Tools

| Inflammatory tinea capitis | Non-inflammatory tinea capitis |

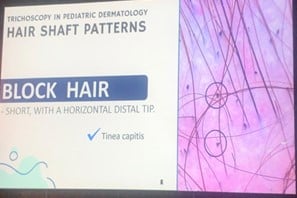

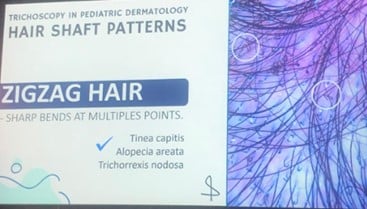

| Follicular pustules | Corkscrew hairs |

| Crusts | White sheaths |

| Perifollicular scaling | Perifollicular and diffuse scaling |

| Linear vessels | Black dots |

| Erythema | Morse code-like hairs |

| Comma hairs /Zigzag hairs | |

Triad of signs (hair loss, scaly patches, peritoneal involvement) = high predictive value (95%).

Differential Diagnosis:

Treatment Recommendations

Common parental questions addressed:

Tracing contact in school is essential.

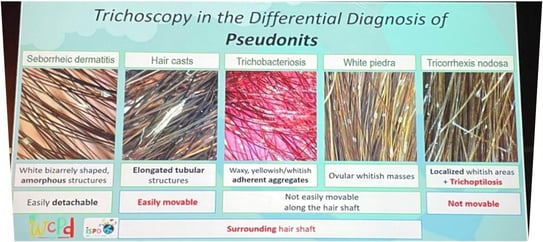

Introduction

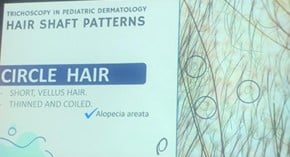

Trichoscopic Differences

True nits: brown with oval heads.

Pseudonits: translucent, grayish, black tips.

Clinical Signs

Treatment

No major new treatments. Conventional therapy remains effective.

Education for parents about lice behavior and contagion is essential.

THERAPY PRESCRIPTION

PERMETRIN

LOTION 1%. Apply and washep up the hair after 10 min, repeat in 1 week

MALATHION

LOTION 0,5%. Apply and washep up the hair after 8-12hs, repeat in 1 week

BENZYL ALCOHOL

LOTION 5%. Apply and washep up the hair after 10 min, repeat in 1 week

IVERMECTIN

LOTION 0,5%. Apply and washep up her hair after 10 min, repeat in 1 week

ORAL TABLETS: 0,2 mg/k/d 2 days, repeat in 1 week

TMS

ORAL: 10 mg/k/d 3 days BID, repeat in 1 week

References:

Speaker: Cecilia Navarro Tuculet (Argentina)

Introduction:

Types of Telogen Effluvium:

Common Triggers of Telogen Effluvium in Children:

Prevalence in Pediatric Population:

Diagnosis and Evaluation:

Differential Diagnosis:

Management:

Take-Home Messages:

References:

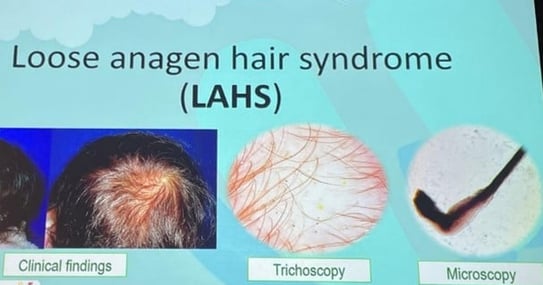

Speaker: Arturo Lopez Yañez Blanco (Mexico)

Definition:

Epidemiology:

Pathophysiology:

Clinical Features:

Diagnostic Findings:

Definition:

Epidemiology:

Pathophysiology:

Clinical Features:

Diagnostic Findings:

Differential Diagnosis:

| Feature | SAS | LAHS |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 2–6 years | 6–10 years |

| Sex predominance | Female | Female > Male |

| Hair appearance | Short (<10cm), sparse, fine |

Fine, short (>20cm), easily pulled |

| Pull test | Negative or mildly positive |

Positive, painless |

| Trichoscopy | Normal | Rectangular/circular black dots, dirty dots |

| Trichogram | ↑ Telogen hairs | Anagen hairs (70%) distorted bulbs and roots |

| Microscopy | Normal hair shafts | Disrupted inner root sheath |

| Pathophysiology | Shortened anagen phase | Poor anchoring of anagen hairs |

| Genetic component | WNT10A mutation (40%) | Keratin gene defects |

| Associated syndromes | Scleroderma, micronychia, etc. | Noonan syndrome, TRPS |

| Prognosis | Benign, improves with age | |

| Minoxidil use | Possible if psychosocially indicated | |

References:

Cranwell WC, et al. Loose anagen hair syndrome: Treatment with systemic minoxidil characterised by marked hair colour change. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59(4):e286-e287.

Lemes LR, et al. Topical and oral minoxidil for hair disorders in pediatric patients: What do we know so far? Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6):e13950.

Starace M, et al Short anagen syndrome: A case series and algorithm for diagnosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38(5):1157-1161

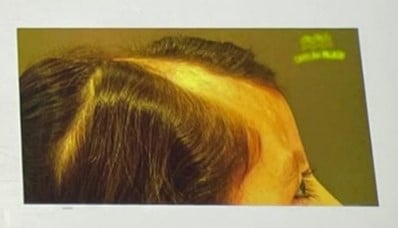

Speaker: Miguel Marti (Argentina)

Common symptoms:

Clinical signs:

Clinical presentation:

| Treatment Modality | |

|---|---|

| Topical corticosteroids | First-line therapy |

| Intralesional corticosteroids | Effective in localized disease |

| Systemic corticosteroids | In more severe cases |

| Hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate | Reserved for refractory cases |

Clinical characteristics:

References:

Speaker: Lizet Rojano Fritz (Colombia)

| Patient | 8-year-old female. No relevant personal or familiar medical history |

|---|---|

| Initial Dx | Alopecia areata (Dec 2024) |

| Treatment | Clobetasol + Prednisone → No response |

| Culture | Positive for Microsporum canis |

| Treatment 1 | Terbinafine x 3 months |

| Follow-up | Persistent central alopecia → repeat trichoscopy: black dots, broken hairs |

| Culture | Still positive |

| Treatment 2 | Griseofulvin x 6 months |

| Observation | Vertex with poor regrowth, trichoptilosis, fine hairs |

| Final Dx | Tinea capitis + Trichotillomania (Patient admitted to hair pulling at night) |

Key Point:

Consider dual diagnoses in pediatric alopecia. Always confirm tinea capitis via culture.

Trichoscopy – Findings by Condition

| Feature | Trichotillomania | Tinea Capitis |

|---|---|---|

| Broken hairs Black dots |

✅✅ | ✅ |

| Trichoptilosis Flame hairs Tulip hairs V sign Microexclamation hairs |

✅ | ❌ |

| Yellow dots | ✅/❌ | ❌ |

| Patient | 8-year-old female |

|---|---|

| History | 5 years of linear facial plaque from vertex to forehead/eyebrow |

| Symptoms | Social withdrawal, no medical history |

| Biopsy | Linear morphea |

| Trichoscopy | Loss of Follicular openings, broken hairs, black dots, pink areas, pili torti. |

| MRI | Thinning of subcutaneous tissue (scalp & facial region) |

| Autoimmune panel | Negative |

| Treatment | Hair transplant after 4 years of inactive lesion |

| Result | Successful regrowth, improved self-esteem |

Key Point:

Hair transplantation can be effective in inactive morphea with no ongoing inflammation.

| Patient | 15-year-old female |

|---|---|

| Hx | Congenital hypotrichosis |

| Trichoscopy | Normal |

| Trichogram | Dystrophic anagen bulbs |

| Phenotypic Features | Bulbous nose, cone shaped epiphyses hands and feet, maxillary prognathism, thin upper lip |

| Genetic Test | Deletion at chromosome 8q24.12 |

| Dx | TRPS Type I |

| Treatment | Topical minoxidil → Good hair density at 6 months |

Key Point:

In congenital hypotrichosis, always assess for syndromic features and genetic testing.

References:

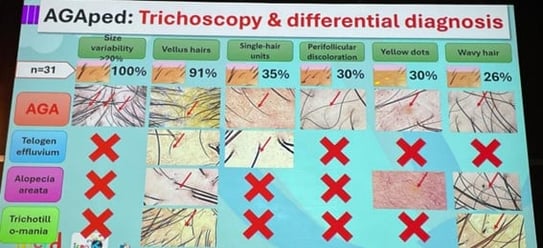

Speaker: Luis Sanchez Dueñas (Mexico)

| Feature | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Hair diameter variability | 100% |

| Vellus hairs | High |

| Yellow dots | Occasional |

| Peripilar sign | Common |

| Wavy hairs | Present |

| Focal atrophy | Rare |

| Indication for Referral | Recommended Action |

|---|---|

| Pre-pubertal onset | Endocrine referral |

| Male with female pattern hair loss |

Hormonal panel |

| Female with signs of hyperandrogenism |

Hormonal panel |

| Suggested labs | Testosterone, DHEA-S, SHBG, LH/FSH, Vitamin D, Glucose, Insulin |

Differential Diagnosis: Telogen effluvium, Alopecia areata, trichotillomania

First-line (Both sexes):

If partial response:

Adjuncts:

Advanced therapy (if poor response):

| FEMALE | MALE | |

| PREPUBERAL | TOPICAL MINOXIDIL 2% | |

| PUBERAL | TOPICAL MINOXIDIL 5% | |

| PARCIAL IMPROVEMENT | Oral minoxidil 0,25-0,5 mg/d Topical Finasteride Topical/Oral Espironolactone |

Oral minoxidil 1-2,5 mg/d Topical Finasteride |

| LIMITED IMPROVEMENT | Oral Finasteride 2,5 mg/d |

Oral Finasteride 1 mg/d |

| Medication | Event | Action Taken |

|---|---|---|

| Oral Finasteride | Gynecomastia (Male) | Stopped → Reversible |

| Oral Minoxidil | Trichomegaly (Excess lashes) | Dose reduction |

References:

Speaker: Sonia Ocampo-Garza (Mexico)

| Group | Clinical Pattern | First-line Treatment | Alternative Options |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | <50% scalp, mild activity, with regrowth | Topical corticosteroids + Minoxidil | Anthralin, intralesional triamcinolone, dexamethasone pulses |

| 2 | >50% scalp, high activity/resistance/ ophiacean pattern | Oral dexamethasone + Topical clobetasol or minoxidil | Methotrexate, Cyclosporine, Hydroxychloroquine |

| 3 | Totalis/Universalis | Contact immunotherapy ± Topical steroids | JAK inhibitors, oral steroids, methotrexate |

Systemic Corticosteroids

| Type | Dose | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Topical | 2–5% | Widely used |

| Oral | 0.5 mg/day | 71% improved in case series (hypertrichosis most common AE) |

Agents:

Protocol:

Adverse Events:

| Drug | JAK Target | Pediatric Use | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tofacitinib | Pan-JAK | Off-label | 87% response in 31 patients |

| Baricitinib | JAK1/2 | Off-label | 68% SALT reduction |

| Ritlecitinib | JAK3/TEC | FDA-approved ≥12 years | SALT <20 in 25–50% at 48 wks |

| Extent | Activity | Primary Approach | Secondary Options |

|---|---|---|---|

| Localized | Active | Topical corticosteroids + Minoxidil | Anthralin |

| Inactive | Immunotherapy | ||

| Extensive | Active | Systemic corticosteroids, JAK inhibitors (Ritlecitinib: approved 12 yo), Immunosuppressants | |

| Inactive | Immunotherapy or JAK inhibitors, Systemic corticosteroids |

References:

Speaker: Lawrence Eichenfield (USA)

Despite recent advances in systemic agents, topical care remains foundational in AD management, even in patients on systemic treatment.

Topical therapy includes:

A critical point raised is that new topical agents are typically studied against vehicles, rather than active comparators like corticosteroids, and usually as monotherapy, which doesn’t reflect real-world practice where combination therapy is common.

The speaker's core message to patients is to aim for long-term disease control, defined as:

Topical corticosteroids remain first-line treatment in many cases.

Steroid phobia is discussed with a notable shift from concern about atrophy to a growing belief in "topical steroid addiction" (TSA). The speaker highlights the video “Skin on Fire” as an example of this messaging. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GuaBbsL1qKA)

While topical steroid withdrawal syndrome (TSW) is a recognized phenomenon, particularly in adults (rare in pediatric population) with long-term use, the concept of widespread topical steroid addiction lacks evidence.

A Swedish internet survey of self-identified TSW patients (recruited via Facebook) reported:

Clinical trial data may overstate perceived effectiveness. In a study of BID mid-potency corticosteroids for 4 weeks:

These results reflect modest short-term efficacy even for traditional agents, reinforcing the need for novel therapies.

1. Topical Ruxolitinib (JAK1/2 Inhibitor)

Pediatric Data: In 2–12-year-olds, ~56% achieved clear/almost clear with BID application.

2. Tapinarof (Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Agonist)

Long-term data:

3. Crisaborole (Topical PDE4 Inhibitor)

4. Roflumilast (PDE4 Inhibitor)

| Formulation | Indication | Age | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.3% cream | Psoriasis | ≥6 | First approval |

| 0.3% foam | Seborrheic dermatitis | Adult | Newer formulation |

| 0.15% cream | Atopic dermatitis | ≥6 | Recently approved |

| 0.05% cream | AD (age 2–5 study) | 2–5 | Not yet approved |

5. Delgocitinib (Pan-JAK Inhibitor)

Current Topical Options

Cost and Access Challenges

Combination Therapy and Real-World Practice

References:

Speaker: Carsten Flohr (United Kingdom)

While advanced therapies in atopic dermatitis (AD) are gaining prominence, conventional systemic treatments remain foundational. This presentation addresses the strategic use of both conventional and newer systemic treatments, framed through clinical evidence and a detailed case study.

Atopic dermatitis is characterized by a chronic itch-scratch cycle that perpetuates inflammation. Exacerbating factors must be managed before initiating systemic therapy:

Effective management should include:

Methotrexate

Cyclosporine

Following suboptimal or complicated responses to conventional agents, advanced therapies may be introduced.

Dupilumab

JAK Inhibitors (e.g., baricitinib, upadacitinib, abrocitinib)

Network meta-analyses (NMAs) provide comparative efficacy and safety data for systemic treatments. One application of this is the clinical decision-support platform [EczemaTherapies.com], designed to:

For patients with multifaceted disease courses or limitations to monotherapy, combination regimens may be necessary.

Case Study Overview:

A patient with severe, early-onset AD (EASI >50 at age 10) demonstrated:

This treatment approach is now published in Pediatric Dermatology as an example of advanced therapeutic integration.

Optimal management of atopic dermatitis requires a nuanced balance between guideline-based strategies, emerging evidence, and real-world complexities. The therapeutic landscape is expanding rapidly, and with it, the opportunity to tailor interventions based on disease severity, comorbidities, and patient preferences—always with a multidisciplinary approach at the center.

References:

Speaker: Elaine Siegfried (USA)

Checklist Prior to Initiating Systemic Therapy:

| Consideration | Description |

|---|---|

| Endotype | E.g., classical AD, contact dermatitis, psoriasis/psoriasiform overlap |

| Non Atopic Comorbidities | Systemic comorbidities, Sleep disruption, HSV (herpes incognito), recurrent otitis media, pneumonia |

| Atopic Comorbidities | Especially ocular (risk for dupilumab-induced conjunctivitis) |

| Corticosteroid Exposure | Topical and systemic |

| Psychosocial Factors | Adherence barriers, anxiety, needle phobia |

| BMI & Development | Consider nutritional status |

| Family History | Atopy, autoimmune, immunodeficiency |

| Access and Cost | May influence therapy selection |

Recognized Subtypes:

| Biomarker | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Total/Specific IgE | Degree of atopic sensitization |

| Eosinophil Count | HES if >1500 × 3 |

| Albumin, Total Protein, Globulins | Nutritional and immunologic markers |

| ANA, Histone | Possible correlation with anti-drug antibody formation |

| Vitamin D | Often deficient; screen for rickets |

| Celiac Screening | Especially in failure to thrive |

| Immunologic Panel | Recurrent infections warrant screening for PID |

Clinical Metrics:

| Response | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Optimal | IGA 0 (clear) |

| Acceptable | IGA 1 (almost clear), stable mild disease |

| Failure | No meaningful improvement (e.g., <2-point IGA drop) |

| Cause | Note |

|---|---|

| Psoriasiform Skewing | Poor response to Type 2 inhibitors |

| Allergic Contact Dermatitis | Difficult to detect, patch testing limited |

| Non-Adherence | Often underestimated |

| Needle Phobia | Impacts biologic use. Management: Home-based behavioral techniques Topical anesthetics Pharmacologic support Mental health referral |

| Anti-Drug Antibodies | Not well studied in AD yet |

| Undiagnosed Infection | May be unmasked post-immunomodulation |

| Primary Immunodeficiency | Often missed without full immune workup |

| Hypersensitivity to Excipients | E.g., polysorbates (noted in most biologics) Polysorbate 80 - Dupilumab, tralokinumab Polysorbate 188 - Nemolizumab |

| Clinical Clue | Consideration |

|---|---|

| Persistent inflammation | Increase topical steroid or add systemic |

| Injection refusal | Oral JAKi or systemic alternatives |

| Excipient reaction | Switch class if possible (not always feasible) |

| Long-term JAKi risk | Transition back to biologic when stable |

| Poor response to dupilumab | Transition to JAKi (e.g., upadacitinib) |

| Allergic contact dermatitis phenotype | Patch testing, methotrexate |

| Suspected anti-drug antibody | Switch to a different class (e.g., JAKi) |

| Psoriasiform phenotype | IL-12/23 blockade (e.g., ustekinumab) may be more effective |

| Adherence issues | Simpler regimens, oral options |

References:

Speaker: Amy S. Paller (USA)

1. Topical Therapies: Evolving Options

| Agent | Status | Age Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roflumilast | Emerging | Likely expanding | Minimal stinging/burning |

| Ruxolitinib | Approved | ≥12 years | Potential for younger use in future |

| Tapinarof | Approved | ≥2 years | Low irritation profile |

2. Novel Targets and Pathways

3. Drug Delivery Innovations

| Method | Limitation |

|---|---|

| Microneedles | Not feasible for high-volume biologics |

| Needle-free injectors | Volume limitations (e.g., dupilumab = 2mL) |

| Sensor-triggered feedback devices | Potential for behavioral intervention |

4. Systemic Therapies: Present and Future

5. Itch as a Therapeutic Frontier

| Pathway | Agent or Target |

|---|---|

| IL-31 | Nemolizumab |

| IL-4/IL-13 | Dupilumab, JAK inhibitors |

| Substance P | Failed trials so far |

| Proteases (e.g., V8 protease) | Antiplatelet drugs as novel topicals |

| PAR2 activation | Calocrine inhibition under study |

6. Remote Monitoring & Digital Trials

Remote Clinical Trials:

Feasible with:

Wearable Technology:

Tracks:

Examples:

8. Next-Gen Technologies:

| Technique | Application |

|---|---|

| Proteomics (5,000 proteins) | Serum analysis from small blood volumes |

| Single-cell transcriptomics | High-resolution skin data |

| Microbiome swabbing | Genomics and proteomics |

| Detergent-based epidermal swabbing | Non-invasive immune profiling |

| Area | Future Outlook |

|---|---|

| Therapeutics | More non-steroidal topicals, pain-free biologics, small molecule inhibitors |

| Monitoring | Objective wearable sensors, real-time feedback |

| Access & Equity | Need for cost reduction and global availability |

| Clinical Trials | Move toward remote, tech-enabled designs |

References:

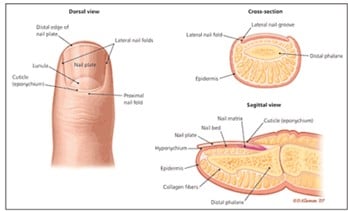

Speaker: Jane Bellet (USA)

1. Nail Anatomy Review:

2. When to Biopsy:

3. Pediatric Considerations:

4. Pre-op Planning:

5. Anesthesia Techniques:

6. Tourniquet Options: bloodless field

7. Common Procedures:

A. Punch Biopsy:

B. Partial Proximal Nail Avulsion:

C. Nail Matrix Shave Excision:

8. Specimen Handling:

9. Tourniquet Removal:

"Most important part of your day."

10. Bandaging Tips:

11. Post-op Care:

12. Special Pediatric Considerations:

13. When Not to Operate:

References:

Speaker: Robert Silverman (USA)

Dermoscopy clues:

Topical:

Systemic:

References:

Speaker: Judith Dominguez Cherit (Mexico)

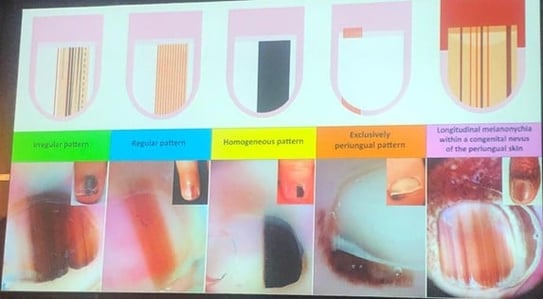

Longitudinal melanonychia (LM) in pediatric patients is a diagnostic challenge. While well-studied in adults, limited data is available in children. The condition may be caused by either melanocytic activation (racial/ethnic or functional) or proliferation (e.g., nevi, melanoma).

| Feature | Adults | Children |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnic melanonychia | Common, especially in darker skin types | Rare, even in darker skin types |

| Melanoma risk | LM may be an early sign | Extremely rare |

| Diagnostic criteria | Well-established | Often unreliable when applied to children |

| Histology appearance | Predictive | May mimic melanoma, even when benign |

BRAFV600E, HMB-45, and PNL2 staining may assist in differentiating between benign and malignant melanocytic lesions. Negative BRAFV600E findings are typically associated with benign nevi.

References:

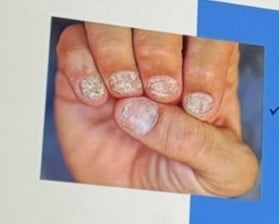

Speaker: Maria Sol Dia (Argentina)

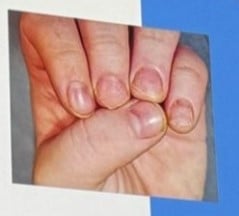

Two clinical contexts:

Dermatologic associations:

Systemic associations:

Clinical Subtypes

| Subtype | Description |

|---|---|

| Opaque Trachyonychia | Most common and severe. Nails appear rough, thin, with longitudinal ridging, and loss of shine. |

| Shiny Trachyonychia | Intermittent inflammation with glassy appearance, light reflection, and fine ridging. |

Common findings in both types:

Clinical Approach:

Tools:

Biopsy:

| Approach | Indication |

|---|---|

| Observation | Most pediatric cases resolve spontaneously within 6 years |

| Topical treatments | Cosmetic concern or associated dermatoses |

| Intralesional corticosteroids | Refractory localized disease (painful, may be distressing) |

| Systemic therapy | Severe or associated with psoriasis, alopecia areata, etc. |

Common topical agents:

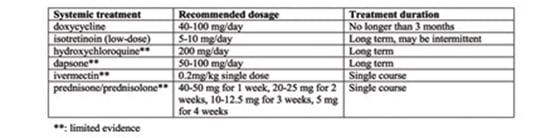

Systemic agents in severe/associated cases:

5-year-old boy with progressive nail roughness, previously treated with various topicals without improvement.

4-year-old girl with a history of atopic dermatitis

References:

Speaker: Lourdes Navarro Campoamor (Spain)

Diagnostic Importance of Nails in Children

Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail fold

Congenital malalignment of the toenail

Congenital anonychia

Iso-Kikuchi Syndrome

Nail-Patella Syndrome

Pachyonychia Congenita

Tuberous Sclerosis Complex

Darier Disease

Melanonychia & Fibromas

| Finding | Possible Associated Conditions |

|---|---|

| Triangular lúnula | Nail Patella Syndrome |

| Micronychia | Iso-Kikuchi, Nail Patella Syndrome |

| Anonychia/ Micronychia index fingers |

Iso-Kikuchi |

| Thickened toenails | Pachyonychia congenita |

| Periungual fibromas | Tuberous sclerosis complex |

| Longitudinal red/white streaks, distal wedge-shaped subungual keratosis, V shaped notch |

Darier disease |

References:

Speaker: Kelly Cordoro (USA)

Speaker: Henry W. Lim (USA)

Photodermatoses are skin disorders caused or aggravated by sunlight.

Categories:

Focus on:

1. Polymorphous Light Eruption (PMLE)

Clinical Features:

Variants:

Diagnosis:

Pathophysiology:

Management:

2. Actinic Prurigo

Treatment:

3. Hydroa Vacciniforme (HV) & HV-like Lymphoproliferative Disease

| Classical Hydroa Vacciniforme (HV) | HV-like Lymphoproliferative Disease |

|

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Rare | Severe variant |

| Age of Onset | Childhood | Childhood or adolescence |

| Skin Lesions | Papulovesicular eruptions healing with vacciniform scars | Lesions on sun-exposed and non-exposed areas |

| Systemic Symptoms | Absent | Facial edema, fever, lymphadenopathy |

| Association with EBV |

Strong | Present |

| Photosensitivity | May show UVA sensitivity on phototesting | Not specifically reported |

| Prognosis | Variable, treatment is challenging | Risk of progression to lymphoma |

| Main Treatment | Photoprotection | Onco-hematological management |

4. Solar Urticaria

Clinical Tip:

Always evaluate patients immediately post-exposure/testing — waiting 24 hours can miss the diagnosis.

Treatment:

5. Erythropoietic Protoporphyria (EPP) & X-linked Protoporphyria (XLP)

Pathophysiology:

Clinical Clues:

Rationale: Blocks porphyrin accumulation upstream in the pathway.

| Condition / Type | Typical Age of Onset | Clinical Morphology | Diagnosis | Treatment / Management | Key Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphous Light Eruption (PMLE) | Children, adolescents (more common in teens) | Papules, vesicles; morphology varies with skin phototype | Clinical (based on history and morphology); phototesting often normal | Photoprotection, topical corticosteroids, narrowband UVB, oral prednisone (for flares) | Delayed onset post-sun exposure; improves with progressive sun exposure ("hardening") |

| Actinic Prurigo | Childhood | Cheilitis, conjunctivitis, lichenified papules on sun-exposed skin | Clinical evaluation | Photoprotection, topical/oral corticosteroids, thalidomide, UVB, dupilumab (experimental) | Latin America; intense sun exposure |

| Classic Hydroa Vacciniforme (HV) | Children | Papules, vesicles, crusting; vacciniform scarring | Clinical, EBV association possible |

Photoprotection, symptomatic care | Permanent scarring; severe phototoxic response |

| HV-like Lymphoproliferative Disease | Children and adolescents | HV-like lesions on both sun-exposed and non-exposed skin; facial edema, fever, lymphadenopathy | Clinical + biopsy + hematologic | Oncology referral, close monitoring | May progress to lymphoma (~10%); high mortality (~40%); more severe in Latin America |

| Solar Urticaria | Children, adolescents, adults |

Wheals in sun-exposed areas; rapid onset (minutes) | Clinical + immediate post-exposure evaluation | Antihistamines, omalizumab, photoprotection | Triggered even by visible light; resolves quickly but recurs with re-exposure |

| Erythropoietic Protoporphyria (EPP / XLP) | Early childhood |

Pain, burning, erythema shortly after sun exposure; chronic changes on knuckles and face | Elevated protoporphyrin IX levels; genetic testing | Afamelanotide (implant), Derzimegalone (oral), glycine transporter inhibitors (in trials), photoprotection | Major therapeutic advances; improves quality of life significantly |

References:

Speaker: Jean Bologna (USA)

| Term Used | Notes |

|---|---|

| Speckled Lentiginous Nevus (SLN) | Preferred by some clinicians; emphasizes clinical pattern. |

| Nevus Spilus | More commonly used in literature (PubMed ratio 2:1); literally means “stained spot.” |

| Other terms | Excessive terminology noted; need for standardization emphasized. |

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Size | Typically 3–4 cm in diameter |

| Base | Café-au-lait macule-like background |

| Overlay | Lentigines, junctional nevi, compound nevi |

| Evolution | More "dots" appear with age; may initially be subtle at birth |

| Distribution Patterns | May follow Blaschko's lines or block-like patterns; not always checkerboard |

| Syndrome/Entity | Association with SLN |

|---|---|

| PPK (Phacomatosis pigmentokeratotica) | Papular SLN |

| PPV (Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis) | Macular SLN |

| Neurocutaneous melanocytosis | Can occur in patients with medium-sized CMN arising within SLN |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | Reported in a patient with Spitz nevi within SLN (rare) |

| Noonan syndrome (RASopathies) | Mentioned as having overlapping features |

| Argument | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Congenital lesion | Lesions follow embryological patterns (e.g., Blaschko's lines); hybrid presentations support this. Evidence supports congenital origin |

| Apparent "acquisition" | Hypopigmented base may be subtle at birth; speckling appears later, leading to misclassification |

References:

Speaker: Aniza Giacaman Contreras (Spain)

| Structure | Description |

|---|---|

| Dots | Small pinpoint areas of pigmentation. |

| Globules | Larger than dots, may vary in shape; correspond to melanocytic nests. |

| Lines | Can form distinct dermoscopic patterns such as networks or branches. |

| Pigmented Network | Reflects melanin in keratinocytes at the dermoepidermal junction. |

| Cobblestone Pattern | Globules clustered in a mosaic-like pattern, commonly seen in CMN. |

| Target Structures | Globules within a network with central dots; may suggest melanocyte apoptosis. |

| Blue/Gray Dots | Indicate melanocyte apoptosis or dermal involvement. |

| Vessels | Presence may vary by lesion evolution; can include coarse vessels. |

| Hypertrichosis | Often associated with congenital nevi, increasing with age. |

| Location | Common Patterns |

|---|---|

| Head | Homogeneous pattern |

| Trunk | Predominantly globular pattern |

| Extremities | Reticular or mixed globular-reticular pattern |

| Palms/soles | Parallel ridge or furrow patterns, “peas-in-a-pod” appearance |

Classic Globular Pattern

Mixed Network and Globules

Changes Over Time

Acral Areas (Palms, Soles)

Nail Matrix Involvement

| Scenario | Clinical Course |

|---|---|

| Nodules stable over years | Often benign if no suspicious dermoscopic features are present. |

| Cobblestone globules without atypia | Favor benign course; continued monitoring recommended. |

| Nodules with blue coloration | May raise concern; histology may still be benign. |

| Rapidly growing nodules in short time | Biopsy warranted to rule out malignancy (e.g., atypical Spitz tumor). |

References:

Speaker: Julia Schaeffer (USA)

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN) | Present at birth or within the first few weeks of life |

| Size-based classification | Based on projected adult size: small (<1.5 cm), medium (1.5–20 cm), large (>20 cm), giant (>40 cm) |

| Targeted CMN / Congenital-like nevi | Lesions appearing within the first 2–3 years; histologically and molecularly similar to true congenital nevi |

Common Dermoscopic Patterns by Location

| Scalp |

|

| Trunk |

|

| Acral |

|

| Nails |

|

| Feature | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Globular pattern | Typical of CMN; benign feature |

| Reticular/blue-gray globules | Seen in deeper melanocyte proliferation; not always concerning |

| Target globules | Globules within network; associated with melanocytic activity |

| Fibrillar brush pattern (nails) | Common in children; benign |

| Vascular features | Can appear over time; not always suggestive of melanoma |

| Risk Estimate | Evidence |

|---|---|

| < 0.5–1% lifetime risk | Systematic reviews & cohort data (e.g., 15-year risk: ~0.007%) |

| Melanoma onset | Typically post-pubertal; rare in early childhood |

Clinical Monitoring

Indications for Excision

| Indication | Reason |

|---|---|

| Cosmetic/psychosocial | Most common modern indication, especially facial lesions |

| Functional concerns | Lesions near joints, eyelids, etc. |

| Changes suggestive of malignancy | Focal color, texture, or vascular changes |

| Parental anxiety | When psychological impact is high and persistent |

Excision Techniques

Laser Therapy

Topical therapies

Timing of Excision:

| Lesion Type | Management Note |

|---|---|

| Halo Nevi | Benign |

| Nodular components | Require thorough history and monitoring |

| Scalp lesions | Tends to fade |

| Acral/Nail lesions | Recognize benign dermoscopic patterns |

- No intervention needed unless atypical features present

- Avoid premature biopsy

- Biopsy only if concerned

References:

Speaker: Fatima Giusti (Argentina)

The speaker presented their experience with digital dermoscopy in pediatric dermatology, emphasizing the need for well-defined clinical indications. The presentation was based on a retrospective study conducted at a tertiary hospital with expertise in both digital dermoscopy and pediatric care.

Demographics & Skin Type

Follow-up & Usage

Risk Factors & Clinical Syndromes

Notably, the prevalence of atypical mole syndrome was significantly higher than in published pediatric cohorts, suggesting potential benefit from structured digital follow-up.

Dermoscopic Patterns

Indications for Digital Dermoscopy

Excision & Histopathology

Findings support the role of digital dermoscopy in avoiding unnecessary surgery while still identifying clinically significant lesions.

Nevus Count

Genetic Conditions

References:

Speaker: Elena Hawryluk (USA)

| Size Category | Lifetime Melanoma Risk |

|---|---|

| Small/Medium CMN | <1% Risk mostly post-puberty |

| Large CMN | ~2% |

| Giant CMN with satellites | 6–15% Highest risk group |

Definition & Risk:

Imaging Strategy:

| Criteria (vary across guidelines) |

|---|

| >3 cm CMN or ≥25 CMN |

| >1 CMN regardless of size |

| Giant CMN, multiple medium CMN |

| ≥4 CMN associated with abnormal CNS findings (Mass General cohort) |

MRI screening guidelines remain non-standardized and are resource-dependent across regions. Shared decision-making with parents is critical.

References:

Speaker: Veronica Kinsler (United Kingdom)

This presentation provided an in-depth review of the genetic mechanisms underlying congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN), focusing on mosaic mutations, especially NRAS, BRAF, and BRAF fusion genes—and their clinical significance. The talk also explored the emerging role of targeted therapy, particularly MEK inhibitors, in treating patients with problematic CMN phenotypes.

| Gene | Prevalence | Mutation Type | Clinical Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| NRAS | Most common | Missense mutations |

Found in skin, CNS, and tumors; consistent across tissues |

| BRAF | Less common | Missense mutations | Often associated with numerous soft dermal nodules |

| BRAF fusions | Newly recognized subgroup | Gene fusion (varied partners) | Often associated with multinodular, treatment-resistant CMN |

| Key Characteristics |

|---|

|

References:

Speaker: Marius Rademaker (New Zealand)

| Rosacea | Perioral Dermatitis (POD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Common Presentation | Facial erythema, flushing, papules/pustules | Papules around mouth, nose, and eyes |

| Flushing | Nearly universal | Usually absent |

| Ocular Involvement | Common (Blepharitis, conjunctivitis) |

Not typical |

| Comedones | Absent | |

| Demodicosis | Possible | |

| Symptoms Description | Burning or stinging | Painful itch |

| Worsened by topical corticosteroids | Yes | |

General Principles

Topical Therapies

Systemic Therapies

Antibiotics: Use with Caution

Isotretinoin (off-label)

Oral Ivermectin

Resume:

References:

Speaker: Irene Lara Corrales (Canada)

1. Steroid-Induced

2. Targeted Therapies (e.g., EGFR & MEK inhibitors)

3. JAK Inhibitor-Induced (JAK-ny)

1. Pityrosporum (Malassezia) Folliculitis

2. Gram-Negative (Hot Tub) Folliculitis

| Feature | Acne | Acneiform Eruption |

|---|---|---|

| Comedones | Present | Absent |

| Onset | Gradual | Sudden, within days–weeks |

| Distribution | Variable | Symmetric, folliculocentric |

| Triggers | Endogenous | Drug or infectious exposure |

References:

Speaker: Maria Lertora (Argentina)

1. Traditional Acne Pathogenesis Expanded

2. Microbiome Diversity in Healthy vs. Acne Skin

3. Microbial Interactions

4. External Influences on the Microbiome

Commonly Studied Probiotic Strains:

1. Oral Probiotics

2. Biome-Friendly Topical Care

3. Personalized Acne Management

References:

Speaker: Agnes Schwieger (Switzerland)

Hormonal Background: Acne is often an external manifestation of hormonal shifts, primarily associated with two developmental pathways:

Of these, adrenal androgens—specifically the activation of the HPA axis—are thought to play a more prominent role in early-onset acne. This activation begins around age six and is known as adrenarche. It leads to increased production of DHEAS, a weak androgen that can be converted into more potent forms, promoting sebaceous gland growth and sebum production. This hormonal activity contributes to acne, body odor, and the development of pubic hair.

Clinical Focus: The lecture centers on infantile acne (starting after 8 weeks of age) and mid-childhood acne (ages 1–7), noting that neonatal acne is rare and often misdiagnosed (commonly confused with neonatal cephalic pustulosis).

Clinical Pearls:

| Comedones – Papules | Azelaic acid, topical retinoids + BP |

| Pustules | + topical ATB/ oral ATB (erythromycin) |

| Nodules - Pseudocysts | oral ATB, oral retinoid (0,3-0,5 mg/k/d) +/- steroid |

Childhood acne, especially in the infantile and mid-childhood periods, warrants thoughtful evaluation. While most cases are benign and hormonally driven, it’s important to rule out systemic or endocrine disorders. With appropriate management, including topical and systemic treatments when needed, these children can achieve excellent outcomes without long-term consequences.

References:

Speaker: Karen Chernoff (USA)

Acne in females may serve as an isolated dermatologic condition or as a potential clinical marker of hyperandrogenism—a state of androgen excess due to ovarian, adrenal, or peripheral sources. Dermatologists play a key role in recognizing clinical signs of hormonal imbalances and initiating appropriate evaluations or referrals.

Hyperandrogenism results from increased androgen production or peripheral conversion. The pituitary gland stimulates the ovaries and adrenal glands, leading to testosterone production, which is converted to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) by 5-alpha-reductase, resulting in clinical manifestations such as acne.

Core Screening Tests

Total & Free Testosterone (if available via LC-MS/MS)

Additional Labs:

Summary Take-Home Points

References:

Speaker: Andrea Zaenglein (USA)

1. Benzoyl Peroxide in Acne Treatment

2. Isotretinoin and Sexual Dysfunction

References:

Speaker: Pearl Kwong (USA)

Examples of Positive Use:

| Case/Trend | Description |

|---|---|

| Foot peel complication | 15-year-old used a trendy foot mask post-injury → developed painful “blue” pus drainage. |

| Do-it-yourself filler | Attempted self-injection based on online tutorial. |

| Tea tree oil misuse | Use in prepubertal boys → gynecomastia. |

| Topical steroid misuse | Pregnant woman applied clobetasol for acne, worsening her condition. |

| Portal abuse | Patients send photos via EMR portal expecting remote diagnosis (e.g., no visible scale or swelling, yet labeled as such by patient). |

| Life coach over medical care | Delay in treating infected ulcerated hemangioma due to parental reliance on unqualified life coach. |

| Failed acne treatment | Long-time patient sought online acne treatments, worsened before returning. |

| Molluscum home remedy | Application of unknown topical remedy caused extreme hyperpigmentation and skin damage. |

| Snail mucin trend | Popular product among teens despite lack of robust evidence. |

Speaker: Veronica Kinsler (United Kingdom)

Study Example – Arteriovenous Malformations (AVMs):

Findings:

siRNA Strategy:

References:

Speaker: Pierre Vabres (France)

The presentation addressed a newly defined group of mosaic disorders characterized not only by clinical features but also by their underlying molecular causes. These disorders, previously described using various clinical terms (e.g., hypomelanosis of Ito, pigmentary mosaicism), are now increasingly classified based on genetic alterations and signaling pathway involvement.

1. mTOR-related Hypomelanosis of Ito

| Gene | Syndrome/Phenotype | Features |

|---|---|---|

| AKT3 | MPPH syndrome | Hemimegalencephaly, PMG |

| PTEN | Cowden/hamartoma syndromes | Macrocephaly |

| PIK3CA | MCAP syndrome | Capillary malformations, overgrowth |

| PIK3R2 | MPPH syndrome | White matter anomalies |

2. RhoA-related Mosaic Syndrome

3. GNA13-related Mosaic Syndrome

Conclusion: Novel somatic variants in mTOR, RhoA, and GNA13 highlight the importance of exome sequencing in skin tissue and contribute to reclassifying these disorders within genetically defined entities.

References:

Speaker: Gianluca Tadini (Italy)

References:

Speaker: Nicole Knoepfel (Switzerland)

Methodology:

| Gene | # of Patients | Clinical Notes | Allele Load | Blood |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GNAS | 3 | One case developed hyperthyroidism at age 12 | Very low | Negative |

| NRAS | 2 | Fair-skinned child with subtle pigmentation, one with nevi | Low | Negative |

| PTPN11 | 1 | Patchy pigmentation, no nevi, pinkish tone | N/A | Negative |

| BRAF | 1 | Segmental pigmentation with nevi | N/A | Negative |

| Chromosomal Mosaicism | 1 | Epilepsy due to carnitine deficiency, 5q gain in skin | N/A | Negative |

Speaker: Aniza Giacaman Contreras (Spain)

| Lesion | Features | Clinical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hypomelanotic macules | Oval, ash-leaf, polygonal, confetti | Often first sign; requires differentiation from vitiligo, nevus anemicus/acromicus |

| Poliosis | White hair patch | Rare but diagnostic |

| Facial angiofibromas | Pink-red papules on central face, sparing upper lip | May resemble acne or rosacea; dermoscopy may show Demodex tails in rosacea |

| Fibrocephalic plaque | Yellowish to brown plaques, scalp or forehead | May be congenital or arise in early infancy |

| Oral fibromas & dental pits | Papules on gums and enamel pitting | Mandates dental referral |

| Peri-/subungual fibromas | Skin-colored or pink papules; nail groove formation | More common on feet; may also appear post-trauma in healthy individuals |

| Shagreen patch | Connective tissue hamartoma with "orange peel" texture | Usually on lumbosacral area |

| UNCOMMON PRESENTATION OF TSC | ||

| Sclerotic bone lesions | Detected radiologically | Important differential: osteoblastic metastases |

|

Red comets

|

Corkscrew-shaped periungual vessels with whitish halo | Seen in adult women with TSC |

| White epidermal nevi (WEN) | Early-life white hyperkeratotic papules | May precede hypomelanotic macules; potential early marker of TSC |

| Folliculocystic and collagen hamartoma |

Congenital scalp tumor; comedo-like openings with tufted hairs | Histology: follicular cysts, collagen bundles, and ruptured follicles |

TSC exhibits a broad phenotypic spectrum, and while many signs are cutaneous, several are subtle or underrecognized. Early detection, thorough examination, and multidisciplinary care are essential for effective management.

References:

Speaker: Maria Rosa Cordisco (USA)

1. Capillary Malformations (CM)

Syndromes Associated with Capillary Malformations

| Syndrome | Key Features | Imaging Findings | Treatment Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCAP Syndrome | Capillary malformation on upper lip/philtrum, megalencephaly, digital anomalies | Polymicrogyria, corpus callosum anomalies, Chiari I | Early neurologic referral, genetic counseling |

| Sturge-Weber Syndrome (SWS) | Facial CM (bilateral V-shaped), leptomeningeal angiomatosis, ocular involvement (glaucoma) | MRI with contrast, eye exams, follow-up imaging for seizures | Early MRI (repeat if negative at <8 weeks), ophthalmologic follow-up |

| GNA11 Mutation | Extensive, reticulated CM, CNS involvement, less aggressive than SWS | MRI brain, less severe neurological involvement | Treat seizures, monitor for glaucoma |

Management of Sturge-Weber Syndrome

Multifocal Capillary Malformations

2. Arteriovenous Malformations (AVMs)

| Key Features | Occurrence | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| AVMs in CNS | 90% in CNS | Surgery, embolization |

| CAMS (Cerebrofacial Arteriovenous Metameric Syndrome) | Unilateral, metameric distribution | Neurosurgical embolization |

3. Hemangiomas with CNS Involvement

| Type | CNS Risk | Key Associations |

|---|---|---|

| Multifocal hemangiomas | Rare CNS lesions (may be asymptomatic) | Screen for visceral involvement |

| Segmental hemangiomas | Risk of PHACE Syndrome | Requires CNS imaging |

PHACE Syndrome

Imaging: MRI head/neck/chest; echocardiogram

Monitoring: Early MRI for stroke risk, less frequent imaging after first year

References:

Speaker: Maria Teresa Garcia Romero (Mexico)

| Pattern Type | Description | Associated Manifestations |

|---|---|---|

| Blaschko’s Lines | Narrow or broad lines following a linear distribution | Found in both melanocytic and non-melanocytic mosaicism |

| Block-like Patterns | Well-defined, localized patches | Associated with neurocutaneous disorders and systemic involvement |

| Lateralization | Unilateral involvement, often localized | Mosaic may manifest only on one side of the body |

| Sash-like Patterns | Diagonal stripes across the body | Typically associated with segmental mosaicism |

| Large Patches | Larger, well-circumscribed areas | Seen in conditions like hypomelanosis of Ito |

References:

Speaker: Camila Downey (Chile)

Embryological & Pathogenic Link:

Types and Severity of RASopathies:

| RASopathy Type | Extent of Cell Involvement | Examples | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germline (all cells affected) | Systemic | Noonan Sme, NF1 | Requires mild/moderate dysregulation to allow survival |

| Mosaic (tissue-specific) | One/few tissues | Shimmelpenning | Severity depends on mutation timing and affected cells |

Genetic Mutations & Dermatologic Lesions:

| Mutation | Associated Lesions | |

|---|---|---|

| K-RAS | Nevus sebaceous, capillary malformations, AVMs | |

| H-RAS | Keratinocytic epidermal nevi, Spitz nevi | |

| N-RAS | Congenital melanocytic nevi | |

| B-RAF | Spitz nevi, congenital melanocytic nevi | |

Clinical Syndromes (“True RASopathies”) with Mosaic Presentation:

Specific dermatologic and extracutaneous findings:

| Syndrome | Mutation | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Shimmelpenning (Linear Nevus Sebaceous Syndrome) | K-RAS | Linear nevus sebaceous, coloboma, PDA, cerebral malformations |

| Keratinocytic Epidermal Nevus Syndrome | Widespread keratinocytic nevi, lymphatic malformation, cardiac anomalies | |

| Oculoectodermal Syndrome | Aplasia cutis, eyelid tags, dermoids, neurodevelopmental delay, cardiac anomalies | |

| Encephalocraniocutaneous Lipomatosis | Alopecia, orbital tags, CNS lipomas, seizures, ocular defects | |

| Phacomatosis Pigmentokeratotica | H-RAS | Sebaceous + melanocytic nevi, scoliosis, rhabdomyosarcoma, epilepsy |

| Cutaneous Skeletal Hypophosphatemia Syndrome | Epidermal nevi, rickets, bone demineralization, eye/CNS involvement |

Genotype-Phenotype Correlations:

Clinical Work-Up Recommendations:

Evaluate for systemic involvement when:

Suggested assessments:

Research Insight:

Key Takeaways:

References:

Speaker: Irene Lara Corrales (Canada)

1. Congenital Melanocytic Nevus (CMN)

2. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC)

3. Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1)

| Disorder | Genetic Pathway | Targeted Therapy | Outcome/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMN (NRAS/BRAF fusion) | MAPK | Trametinib | ↓ lesion bulk, pruritus, erythema |

| CMN (PIK3CA-related) | PI3K-AKT-mTOR | PIK3CA inhibitors | ↓ melanocyte density (early evidence) |

| Tuberous Sclerosis | mTOR | Everolimus / Sirolimus | ↓ renal tumors; variable angiofibroma response |

| EGFR | Afatinib + Everolimus | ↓ SEGA and cortical lesions (preclinical) | |

| – | Prenatal Sirolimus | ↓ fetal rhabdomyomas (case reports) | |

| Neurofibromatosis Type 1 | RAS-MAPK | Selumetinib | ↓ inoperable plexiforms, improved QoL |

| Trametinib (gliomas) | FDA-approved for brain tumors |

References:

Speaker: Maria Agustina Acosta (Uruguay)

General Role & Indications

Phototherapy Modalities

| Modality | Comments |

|---|---|

| Narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) | Most commonly used in children |

| PUVA (Psoralen + UVA) | Rare in pediatrics due to safety concerns |

| Targeted phototherapy | Used for localized lesions |

| Home-based UVB | An emerging alternative with careful supervision |

Pediatric Considerations

Home Phototherapy

Phototherapy vs Biologics

References:

Speaker: Matias Maskin (Argentina)

Phototherapy is now generally used as a second-line therapy or in combination with biologics for severe cases.

Phototherapy is recommended for moderate cases, but systemic biologics are preferred for severe atopic dermatitis

Phototherapy remains a viable option for early-stage cases

The role of phototherapy in pediatric dermatology is evolving. While it remains an essential treatment option for mild to moderate conditions, newer biologic therapies are increasingly becoming the go-to treatments for more severe conditions. Moving forward, phototherapy will likely be incorporated more into combination therapies, making it a valuable tool but no longer a first-line treatment in most cases.

References:

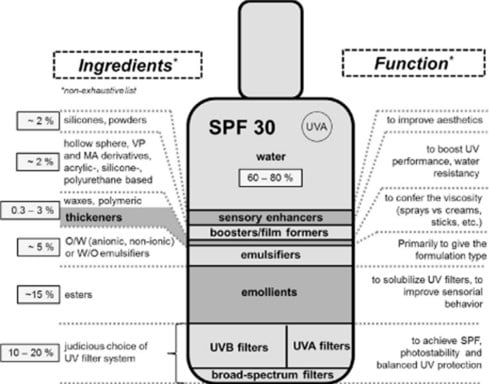

Speaker: Henry W. LIM (USA)

Composition and Effects of Sunlight

| Darker skin: |

Lighter skin:

|

| More and larger melanosomes, individually dispersed | Smaller melanosomes, grouped in keratinocytes |

| Intrinsic SPF ~13 | Intrinsic SPF ~3 |

Family & Cultural Influence

Clinical Correlations

Age-Specific Advice

Practical Challenges

Skin Tone–Specific Recommendations

| Skin Type | SPF Recommendation | UVA Protection | Visible Light Protection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type I–III (Light) | ≥ SPF 50 | Moderate | Not critical |

| Type IV–VI (Dark) | ≥ SPF 30 | Higher preferred | Important (pigmentation risk) |

Sunscreen on exposed areas (SPF and spectrum tailored to skin type)

+

References:

Speaker: Antonio Torrelo (Spain)

Overview: Phototherapy is a valuable tool in dermatology, including pediatric cases, though protocols are often adult-centered. Its application in children must be individualized, especially in rare or severe cases. The following summarizes insights into photodermatoses such as Polymorphic Light Eruption (PMLE) and Actinic Prurigo (AP), with recent treatment updates.

Systemic antioxidants: Safe for children (e.g., beta-carotene), less standardized in children.

| Condition | Presentation in Children | First-line Therapy | Emerging/Alternative | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphic Light Eruption (PLE) | Rare, mild; juvenile spring eruption | UV-A protection, antioxidants | Omalizumab (adults), topical tacrolimus |

Desensitization rarely used in <7 years |

| Actinic Prurigo (AP) | Common in Latin America; rare in Europe | Steroids (low response), avoidance | Talidomide, JAK inhibitors, nicotinamide | Associated with specific HLA types |

| Photodermatoses (refractory) | Severe, resistant to topical therapy | Photoprotection, antioxidants | JAK inhibitors, nicotinamide | Requires individualized approach |

References:

Speaker: Fernando M. Stengel (Argentina)

Pollution Sources

Coral Reefs and UV Filters

Geographic Evidence

| Compound | Category | Environmental Concern | Human Safety | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxybenzone (BP-3) | Organic | Coral bleaching, endocrine disruption in fish | Potential endocrine disruptor | Banned in several regions |

| Octinoxate | Coral toxicity, marine pollution | Moderate absorption, hormonal data | Banned in reef-sensitive areas |

|

| Octocrylene | Marine toxicity, bioaccumulation | May accumulate in tissue | Still widely used in many countries | |

| Titanium Dioxide |

Inorganic (mineral) |

Precipitates in seawater, low coral interaction | Not absorbed dermally | Considered safe; used in children |

| Zinc Oxide | Similar to TiO₂ – precipitates, low coral impact | Not absorbed dermally | Recommended for pediatric use | |

| New Organic Agents | Organic hybrid | Limited data | Under investigation | Safer formulations under development |

References:

Report written by Dr Paola Stefano (Paediatric Dermatologist, Argentina)

Panellists: Dr Juan Carlos Lopez Gutierrez (Spain), Dr Eulalia Baselga (Spain), Dr Isabel Colmenero (Spain), Dr María Rosa Cordisco (United States)

In this session, Dr Maria Rosa Cordisco first announced the publication of the book ‘Anomalías vasculares en la infancia’, in Spanish, with the participation of international experts in genetics, radiology, dermatology, pharmacology and other disciplines. She explained the importance of interdisciplinary teamwork for the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of these anomalies. Thanks to recent advances in genetics, classifying and diagnosing the different anomalies and establishing treatment with targeted therapies has been possible in these complex patients. Dr Natalia Torres emphasised that the book is up-to-date with the latest diagnostic and therapeutic advances, as well as the latest 2025 ISSVA classification.

In turn, Dr Teplinsky, a Paediatric Radiologist and Coordinator of the Vascular Anomalies Group at Hospital de Pediatría “Prof. Dr Juan P. Garrahan” [“Prof. Dr Juan P. Garrahan” Paediatric Hospital] and of the Centro de Anomalías vasculares del Sanatorio Mater Dei [Mater Dei Sanatorium Vascular Anomalies Centre], announced the creation of the Ibero-American Society for Vascular Anomalies (SIAV). This Society was founded in September 2024, is based in Spain and includes Spanish-speaking countries. This Society’s mission is to promote knowledge in the diagnosis and treatment of vascular anomalies and to foster collaboration among the different specialities and countries in Latin America, thereby contributing to improving the quality of life of patients. Another objective of this Society is to work together in the same language, in order to give correct nomenclature to vascular anomalies, create diagnosis and treatment guidelines and hold meetings to discuss cases. He also reinforced the desire for this new Society to be linked to the parent societies the Spanish Society of Vascular Anomalies (SEAV) and ISSVA (International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies).

Speaker: Dr Natalia Torres (Argentina)

Paediatric Dermatologist. Hospital Dr Juan P. Garrahan, Coordinator of the Vascular Anomalies Interdisciplinary Group - Hospital Dr Juan P. Garrahan - Argentina

The case of a 12-year-old girl was presented for discussion who had been seen for headache, pain and functional impotence of her arm. The patient also had macrocephaly and cognitive deficit. On dermatological examination, she had a vascular-looking, erythematous-telangiectatic lesion with evidence of venous pathways on her forearm from the first years of her life that progressed with her growth, and another lesion in her thoracic region. She had undergone two embolisations and was seeking a second opinion.

Ultrasound showed soft tissue enlargement and dilated vessels with high flow. Magnetic resonance angiography imaging also showed multiple arteriovenous shunts dependent on the subclavian, axillary and brachial arteries.

In addition, she had left ventricular dysfunction secondary to her vascular anomaly which generated volume overload, so she was administered enalapril and the decision was made to perform a new embolisation.

A skin biopsy was performed, confirming the diagnosis of an arteriovenous malformation.

She was administered thalidomide 50 mg/day and contraception was indicated. The patient continued to experience chronic pain and progressive loss of arm function.

The suspected diagnosis was PHOST syndrome (PTEN hamartoma of soft tissue) related to PTEN hamartoma tumour syndrome (PHTS), so a genetic study was requested and, in consultation with Dr Denise Adams, treatment with sirolimus was initiated. During the clinical course, the patient presented with bleeding ulcers and uncontrollable pain, so after an interdisciplinary evaluation, the decision was made to amputate her arm. The patient recovered her cardiac function. She continues to be treated with sirolimus for the chest lesion. In the end, the PTEN gene mutation was confirmed.

It is an underdiagnosed disease which requires early diagnosis to initiate appropriate treatment, and tumours can develop in adulthood.

Dr Juan Lopez Gutierrez suggested a registry of patients with PTEN mutations in order to identify different manifestations and associations in these patients.

Speaker: Dr Maria Laura Cossio (Chile)

Dr Cossio presented the case of a patient with the diagnosis of intracranial arteriovenous malformation with a large secondary cranial defect.

This was a newborn baby girl with congenital erythematous lesions on her scalp and convulsions at one month of age. MRI: right frontotemporal infarction with haemorrhages in the right parenchyma and cranial bone defect.

She initiated treatment with sirolimus as the scalp lesions started bleeding.

A biopsy of the scalp lesion could not be performed for genetic study, due to the associated risk of haemorrhage.

Dr Juan Carlos Lopez Gutierrez believed that MEK inhibitors such as trametinib could be indicated, biopsy of the scalp lesions could be performed if possible or perhaps a genetic blood study could be attempted.

Speaker: Dr Alejandro Celisv (Mexico)

A 29-year-old patient, who has had a bluish tumour on their lower lip since the age of 16 with gradual growth. At the age of 19, the patient presented with significant bleeding. The patient underwent embolisation with coil embolisation of nutrient vessels but continued to bleed and had to undergo vessel ligation. They were administered thalidomide for 1 year and remained stable. Surgery was then performed, following embolisation with resection of the tumour and reconstruction with skin flaps. The patient is currently on thalidomide and asymptomatic.

As comments, emphasis was placed on the early and combination treatment of arteriovenous malformations.

Speaker: Dr Irene Lara Corrales (Canada)

She presented a female patient with CM-AVM (capillary malformation associated with arteriovenous malformation).

This patient was seen at the age of 6 for asymmetric growth in a foot in which she had a capillary malformation (CM).

Genetic testing confirmed RASA1 mutation, both in skin biopsy and in blood. Genetic studies in both parents were negative.

An MRI of the brain and spine showed a cerebral arteriovenous (AV) fistula.

The CNS fistula was embolised, with no recurrence to date.

CM-AVM is an autosomal dominant inherited RASopathy.

Approximately 18% of patients with RAS 1 mutations have AV malformations or fistulas.

Dr Baselga suggested that newly diagnosed patients and adolescents should be asked to undergo follow-up brain and spine MRI scans prior to discharge, even if they are asymptomatic.

Speaker: Dr Felipe Enrique Velasquez Valderrama (Peru)

He presented a one-month-old patient with a congenital, vascular-looking, erythematous-violaceous tumour on the thigh, with a central crust.

The patient was hospitalised for systemic infection. Doppler ultrasound was performed on the tumour: thickened saphenous vein, collateral branches, tumour with venous and arterial components.

Days later the tumour started bleeding. All attempts were made to stop the bleeding, but the patient died from profuse haemorrhage.

Comments from Dr Colmenero: Rapidly involuting congenital haemangiomas (RICH) can have this fatal outcome. When prominent arterial vessels are detected on ultrasound, they should be embolised early.

Coordinator: Dr Agustina Vila Echague

Co-Coordinator: Dr Mirna Erendira Toledo Bahena & Dr Héctor Cáceres Ríos

Speaker: Betina Pagotto (Argentina)

Acne is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the pilosebaceous unit, which mainly affects adolescents and may continue into adulthood. It is estimated that it affects approximately 90% of the population at some point in their lives. Its main predisposing factors include age, skin type, obesity and family history.

Prevalence is almost 100% in adolescence and decreases with age. Its impact goes beyond the skin: it is associated with impaired quality of life, depression and low self-esteem, which highlights the importance of early treatment, especially in inflammatory cases.

The pathogenesis of acne is multifactorial:

Recently, the following new factors have been identified as being involved:

Different technologies have been used for the management of active acne and its sequelae:

Mechanisms of action

These therapies, especially when properly combined, can improve the inflammatory component, reduce bacterial colonisation and treat sequelae with remarkable aesthetic results.

Speaker: Dr Agustina Vila Echague (Salvador)

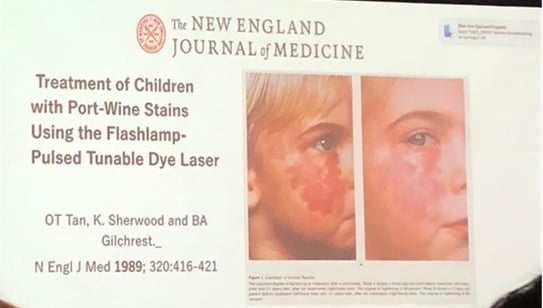

Capillary vascular malformations (CVMs or port-wine stains) are low-flow vascular malformations, present since birth, caused by genetic GNAQ mutation leading to progressive ectasia of the superficial cutaneous vascular plexus. They affect 0.3% of newborns.

Clinical presentation: They can present in different clinical subtypes: from flat, pale pink macules to violaceous, hypertrophic or nodular lesions. A significant percentage of these lesions are associated with Sturge-Weber syndrome, which accounts for approximately 20% of all vascular malformations. Symptoms of this syndrome may not be present at birth, but manifest progressively up to the age of 5. For this reason, performing clinical and neurological examinations is key for at least the first five years of life in patients with facial port-wine stains to confirm or rule out the presence of the syndrome.

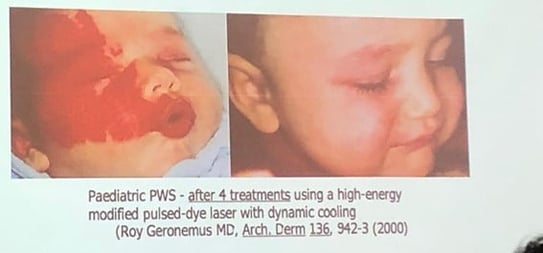

CVMs can be treated with pulsed-dye laser (PDL, 595 nm). Initiating treatments at an early age is recommended, as vessels are more superficial and smaller.

Reference: He HY, Shi WK, Jiang JC, Gao Y, Xue XM. An exploration of optimal time and safety of 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of early superficial infantile hemangioma. Dermatol Ther. 2022 May;35(5):e15406. doi: 10.1111/dth.15406. Epub 2022 Mar 9. PMID: 35199898; PMCID: PMC9285537.

Reference: Geronemus R et al. High fluence modified pulsed dye laser photocoagulation with dynamic cooling of port wine stains in infancy. Arch Derm 2000; 136: 942–943

Speaker: Héctor Cáceres Ríos (Peru)

He initially referred to infantile haemangiomas, benign tumours with endothelial proliferation. They usually onset in the first few weeks of life and grow rapidly for the first 3 months. They then remain stable in growth or grow very little until one year of age and then begin to involute and slowly decrease in size. There are precursor signs in up to 50% of cases: telangiectasias, anaemic macules or bluish spots.

There are small lesions, with no clinical repercussions, and others that are located near vital organs such as the eyes and mouth, for which treatment must be defined.

Clinically, they may be superficial in 60% of cases (“strawberry” variant), deep (bluish in colour) in 15%, or mixed in 25%.

Differentiating them from neoplastic processes such as lymphomas or rhabdomyosarcomas is essential.

As for their origin, they have been found to share the same markers as the placenta, which backs the theory of placental tissue embolisation. GLUT-1, merosin, FcYRII and Lewis Y antigen expression, among others, have been detected, confirming that haemangiomas represent vasculogenesis and angiogenesis processes, influenced by different factors.

Combination therapy: he also mentioned the possibility of combining topical and systemic laser treatments.

Current knowledge about the genetics of vascular anomalies and the availability of effective laser technologies enables a more precise and personalised approach. Early initiation of treatment improves clinical outcomes and quality of life for paediatric patients.

References:

Asilian, Ali1,2,3; Mokhtari, Fatemeh1,3; Kamali, Atefeh Sadat1,3,4,; Abtahi-Naeini, Bahareh1,3; Nilforoushzadeh, Mohammad Ali2,5; Mostafaie, Shayan3,6. Pulsed dye laser and topical timolol gel versus pulse dye laser in treatment of infantile hemangioma: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Advanced Biomedical Research 4(1):p 257, | DOI: 10.4103/2277-9175.170682

Kavitha K. Reddy MD, Francine Blei MD, Jeremy A. Brauer MD, Milton Waner MD, Robert Anolik MD, Leonard Bernstein MD, Lori Brightman MD, Elizabeth Hale MD, Julie Karen MD, Elliot Weiss MD, Roy G. Geronemus MD Retrospective Study of the Treatment of Infantile Hemangiomas Using a Combination of Propranolol and Pulsed Dye Laser. Dermatol Surg Volume39, Issue6. June 2013.Pages 923-933.https://doi.org/10.1111/dsu.12158

Speaker: Dr Mirna Erendira Toledo Bahena (Mexico)

Dr Toledo Bahena first referred to laser advances over the last 30 years that have led to the development of new therapeutic strategies for common paediatric skin conditions. She emphasised laser treatment as a non-invasive alternative to surgical options, and in many cases, it can provide better results.

In expert hands, laser therapy has been shown to be safe in both children and adults. This is very important and receiving specific training in treating paediatric patients is essential.

In the paediatric population, the scope of treatment has been extended to a variety of conditions including vascular and pigmented lesions, inflammatory diseases, scars, vitiligo and for tattoo and hair removal as well.

The laser works by emitting high-intensity monochromatic light, which is absorbed by specific structures in the skin called chromophores. This absorption generates selective thermal destruction of the target without damaging the surrounding tissue. In vascular lesions, the chromophore is haemoglobin, and in pigmented lesions, it is melanin.

In pigmented lesions, the chromophore is melanin; in vascular lesions, it is haemoglobin. Light absorption varies from 250 to 1200 nm, depending on lesion depth.

Q-switched or picosecond lasers fragment the pigment so that it is eliminated by the lymphatic system. These are ideal for many of the conditions we treat in paediatric dermatology, including tattoos.

In pigmented lesions such as naevus of Ota, the gold standard is the Q-switched laser. Nd:YAG, Ruby or Alexandrite lasers are used. These act via photoacoustics, destroying the dermal pigment.

One study reported that approximately 5 Alexandrite laser sessions achieved 50% effectiveness with a low adverse event rate (between 2% and 7.9%). Dr Toledo Bahena reported that, at her hospital, they have treated 15 patients (aged 3–16 years, phototype IV) and assessed their response after several Q-switched Nd:YAG sessions.

They obtained:

• 45% with excellent response

• 13% with moderate response

• 25% with poor response

Only one patient showed residual hyperpigmentation.

The doctor showed several photographs of children treated for naevus of Ota who showed good results.

She also spoke about the excimer laser for pigmentary conditions:

Although it is not strictly a laser, excimer light (308 nm) is a very useful technology for diseases such as vitiligo. It works by inducing apoptosis in lymphocytes and keratinocytes, and stimulates melanocyte migration and melanin production.

It is a safe option that only acts on the epidermis, which is ideal for children and patients with sensitive skin.

References:

Sakio R, Ohshiro T, Sasaki K, Ohshiro T. Usefulness of picosecond pulse alexandrite laser treatment for nevus of Ota. Laser Ther. 2018 Dec 31;27(4):251–255. doi:10.5978/islsm.27_18-OR-22

Mejoría clínica de pacientes pediátricos con nevo de ota utilizando tecnología láser Q-Switched en el Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14330/TES01000761986

Speaker: Jean L. Bolognia (United States)

Dr Jean L. Bolognia proposed a clinical and pathological journey along the “blue brick road”, from congenital sacral dermal melanocytosis to cellular blue naevi, with emphasis on the clinical, histological, genetic aspects and diagnostic implications of these pigmented melanocytic lesions. Entities such as acquired and congenital forms of the naevus of Ota and Ito, as well as the association with neurocutaneous syndromes, malignant potential and therapeutic management were discussed.

1. Congenital dermal melanocytosis (CDM)

2. Naevus of Ota and Ito

Naevus of Ota: also called oculodermal melanocytosis. It involves V1-V2 dermatomes, is usually unilateral and has ocular involvement (50% in mild forms, up to 100% in extensive forms).

Naevus of Ito: similar, but in brachial nerve territories; no ocular involvement.

In addition, she described acquired bilateral naevus of Ota-like macules (ABNOM), also known as Hori’s naevus, a benign dermal melanocytosis characterised by the appearance of blue-brown or slate grey macules on the face, especially on the cheeks, temples and forehead. It is most commonly seen in women of Asian descent after the third decade of life. ABNOM differs from naevus of Ota in that its onset occurs later and there is no involvement of the conjunctiva, mucosa and tympanic membrane.

3. Common genetic aspects

4. Blue naevi

“Common” and “cellular” are histological terms, not clinical ones.

Combined: association of compound naevus with blue naevus (greyish colour).

Histology is key to differentiating benign from malignant forms.

5. Variants and related entities

Congenital dermal melanocytosis and the different types of blue naevi represent a broad spectrum of melanocytic lesions with diverse clinical, genetic and prognostic implications. Detailed knowledge of its clinical presentation, anatomical distribution, histological characteristics and syndromic associations enables an accurate diagnosis to be made, cases at risk of malignancy to be identified, and appropriate follow-up to be implemented, including ophthalmological monitoring and possible CNS imaging in selected patients. Identifying GNAQ/GNA11 mutations and BAP1 loss are key in understanding its biology and potential for malignant transformation.

References:

Cordova A. The Mongolian spot: a study of ethnic differences and a literature review. Clinical Pediatrics 1981 vol 20: 714–719

Romagnuolo M, Moltrasio C, Gasperini S, Marzano AV, Cambiaghi S. Extensive and Persistent Dermal Melanocytosis in a Male Carrier of Mucopolysaccharidosis Type IIIC (Sanfilippo Syndrome): A Case Report. Children (Basel). 2023 Dec 13;10(12):1920. doi: 10.3390/children10121920. PMID: 38136122; PMCID: PMC10742075.

Speaker: Dr Amy Paller (United States)

Pruritus is a common manifestation in a variety of dermatoses, but its treatment in genetic diseases such as ichthyosis (now called epidermal differentiation disorders) and epidermolysis bullosa (EB) represents a considerable clinical challenge.

Up to 17% of children and adolescents report chronic pruritus, and it is even more prevalent in genetic skin diseases. Scales such as the NRS (Numerical Rating Scale) or the VAS (Visual Analogue Scale) have been validated to quantify intensity, including versions adapted for parents of children who cannot self-assess. However, it highlights the need for more holistic assessments that take into account the impact on physical, mental and social health.

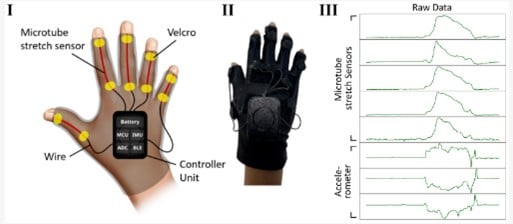

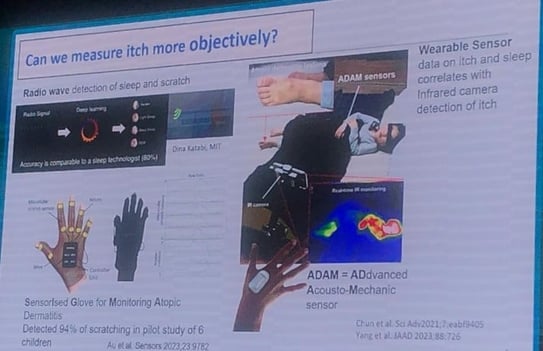

Devices such as sensorised gloves, digital sensors and portable acoustic systems (e.g. ADAM sensor) have been developed that are able to record scratching events during sleep, differentiating these from other movements.

Pruritus is transmitted by C- and A-delta nerve fibres, with endings reaching the epidermis. These neurons express key receptors such as IL-4, IL-13 and IL-31 and communicate bidirectionally with keratinocytes and immunocytes, amplifying or regulating the pruritic stimulus.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) induces pruritus in murine models by producing V8 protease, which activates the PAR-1 receptor on nerve fibres. This pathway, which is independent of histamine and ILs, opens up novel therapeutic opportunities with topical PAR-1 inhibitors.

Up to 93% of patients present with pruritus. In studies with pregabalin, a benefit on neuropathic pain was found, but with little effect on pruritus. In murine models, the use of endocannabinoid system modulators has been explored, showing promising results.

Increased substance P has been documented in the skin of patients with dystrophic EB, correlating with increased pruritus intensity. Neurokinin 1 (NK-1) receptor antagonists such as serlopitant have shown a tendency to reduce pruritus in pilot studies.

A recent survey reported that 45% of patients with EB use tetrahydrocannabinol/cannabidiol (THC/CBD) products, and 64% report improvement of pruritus. Cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors are present in dorsal root ganglia and skin fibres, and alterations in their expression have been identified in animal models.

Current therapies: biologics and JAK inhibitors

This biologic, fully human monoclonal antibody (mAb) targets the α-subunit of the interleukin 4 receptor (anti-IL-4Rα) and is approved for atopic dermatitis. It has been evaluated in an open-label study in patients with epidermolysis bullosa (n=22). At 16 weeks, a significant reduction in mean and severe pruritus was found, as were objective improvements in sleep using recording devices. Response was independent of baseline IgE levels.

In a subgroup with junctional epidermolysis bullosa (collagen VII deficiency), a reduction of more than 4 points on the pruritus scale was documented, with a positive impact on autonomy and quality of life. Safety was favourable, with minimal local reactions and only one case of mild conjunctivitis.

IL-31R antibody (nemolizumab): with therapeutic potential, especially because of the correlation of IL-31 with pruritus in EB.

JAK inhibitors: used off-label (baricitinib, tofacitinib, etc.) with good results in reducing pruritus and lesions in EB, although their risk profile in immunocompromised patients is of concern.

Pruritus is multifactorial in genetic diseases, with complex neuroimmunological mechanisms. The use of objective tools, together with targeted therapies (biologics, cannabinoids, specific pathway inhibitors), opens a new paradigm in the personalised treatment of these patients. Further studies are needed to optimise safe and effective therapeutic strategies in the affected paediatric population.

Reference: